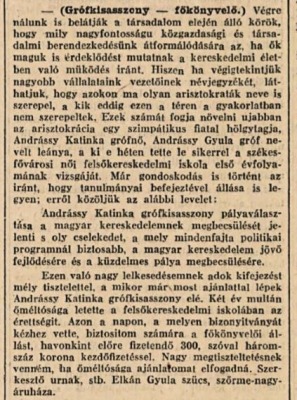

A long-forgotten photo album preserving scene stills of the film featuring young Hungarian aristocrats was brought back to life, and through this an 10-minute fragment of the originally 50-minute-long film has been reconstructed from stills.

Origin of the film – that is, a charitable, amateur performance in 20th century style

Organizers of the charity performance staged to raise money for the Polyclinic and Hungarian aviation, Countess Gyula Andrássy, president of the Polyclinic Association, and Count Béla Rezső Zichy, president of the Aëro Association, decided to implement their plans in a modern and permanent form taking advantage of the increasingly popular new art of the day, film: they made a moving picture featuring amateur players recruited from the aristocracy, which they then distributed all over the country, and even abroad, channelling all revenue thus raised to their charitable causes.

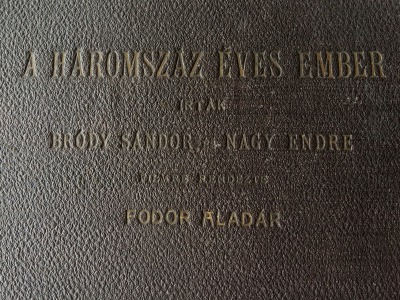

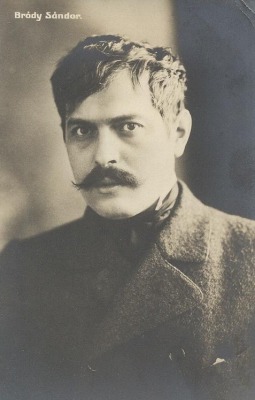

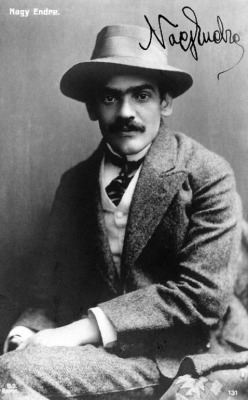

In February 1914, the organizers approached a pair of outstanding figures of contemporary Hungarian literature – Sándor Bródy and Endre Nagy – to write the screenplay. These two departed from the realism trend of Hungarian feature filmmaking that copied Danish social dramas, instead writing a science fiction work complete with time travel and spanning several centuries. The first sci-fi film in the history of Hungarian cinema was born from their screenplay, which did not have many followers in Hungarian film production that was hostile to futuristic films and limited in genres: just 10 of the approximately 600 feature films made between 1912 and 1930 chose a sci-fi theme, and there were even fewer in the period of talkies.

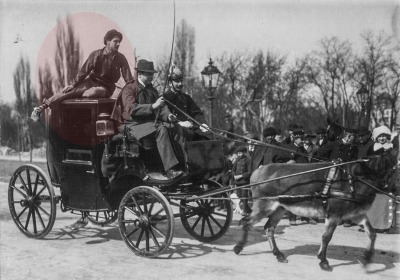

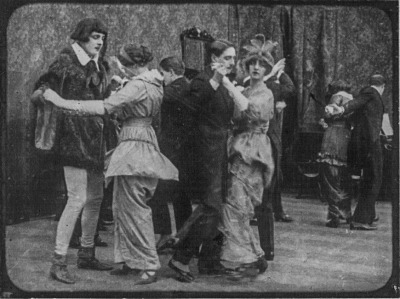

A háromszáz éves ember (The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man) is the story of time travel, and although in this film the time machine is a dream, the direction of time travel is not from the present into the future, as in the Wells novel The Time Machine, nor is it from the present into the past, as in Ferenc Herczeg’s Szíriusz and its film version. Instead, our hero shifts from the past to the present, from the 17th century to the second decade of the 20th century, when the film was made, where he seeks and finds his beloved, who could not be his in the 17th century. Since cinema, a medium that fixes the fleeting moment, is in itself a kind of time machine, with the help of the film we, today’s audience, can also embark on time travel into the past and Budapest of spring 1914, to Stefánia Road close to the long-demolished water tower, to a world of gentlemen riders and early automobiles, to the terrace of the Ritz hotel, the tennis courts of the Park Club, the hangars and monoplanes of Rákosmező airfield. Unfortunately, since this moving picture no longer exists, we have to do all this using the surviving stills from the film.

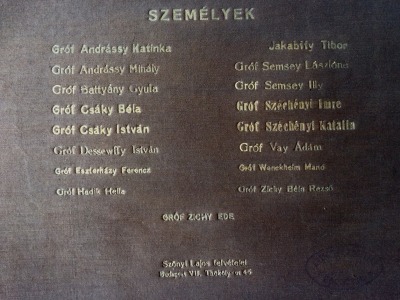

The screenplay for the film was completed in early March 1914. Scene planning and casting were decided by a meeting of aristocrats under the presidency of Countess Gyula Andrássy, Eleonóra Zichy.

Leading roles

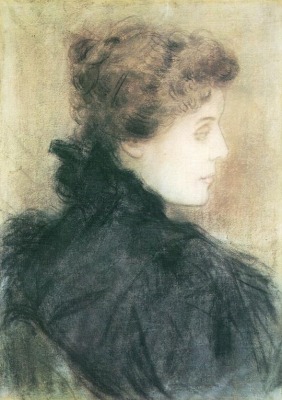

Borbála, the beloved countess, played by:

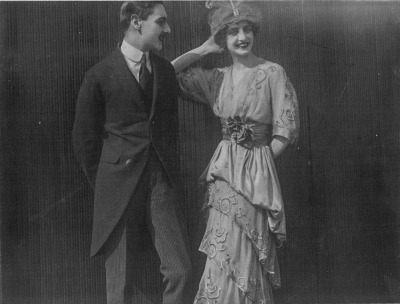

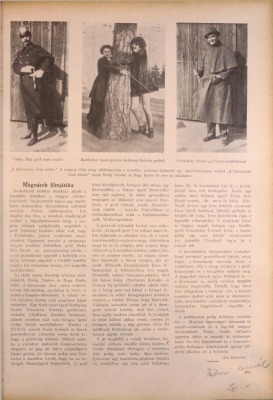

Katinka Andrássy c. 1920: in real life, too, she chose her own husband (photo: Library of Congress)

Countess Gyula Andrássy cast the female lead part to her third, unmarried daughter, Countess Katinka Andrássy (1892-1985), who at that time was one of the most popular members of the Hungarian aristocracy and a figure permanently featuring in the society columns of newspapers. They recounted the most trivial details of her life, her achievements in school examinations and her participation at sports events. Two years prior to the making of the film, news of her attempted suicide caused a sensation, although the family tried to portray it as an accident. However, some sources speculated that Katinka Andrássy meant to kill herself because her parents chose her future husband against her wishes. If this really was the case, then she succeeded in her rebellion: finally, she was able to choose her own partner. In November of 1914, the year the film was shot, she married the far older and radical Mihály Károlyi (who later became known as the ‘red count’), and espoused her husband’s political outlook. Her life thereafter was determined by her marriage. She lived abroad from March 1919 until her death.

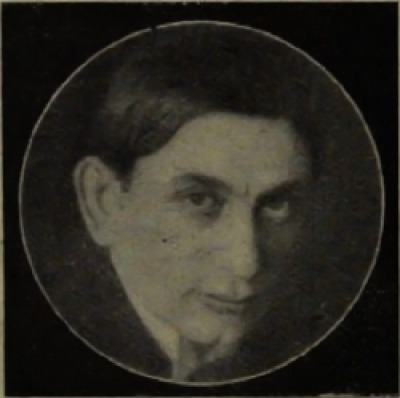

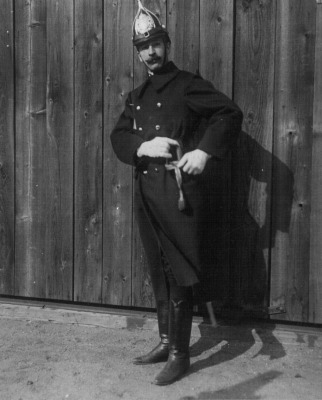

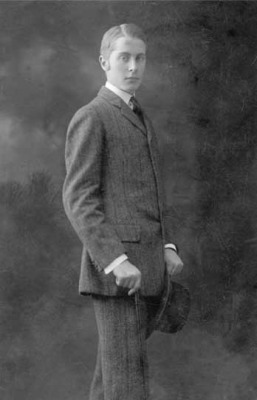

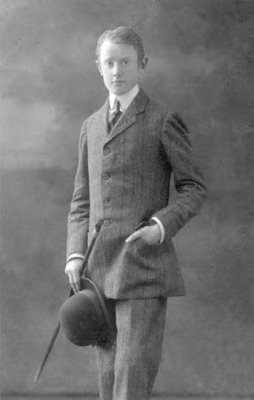

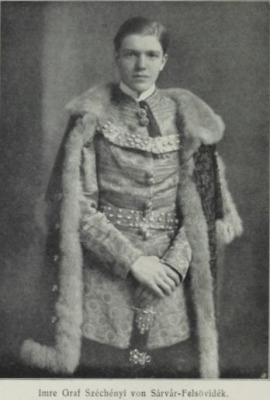

Bálint, the count seeking his beloved in the labyrinth of time:

Gyula Batthyány, painter, considered the most charming man of the period. (photo: Tolnai Világlapja)

The male lead role was played by Count Gyula Batthyány (1887-1959), cousin of Countess Katinka Andrássy and great grandson of Count Lajos Batthyány, martyr of the first independent Hungarian government. The young count was also a society favourite and one of the most elegant men of his day (in 1922, with 14,050 votes, he was elected the most attractive man in the ‘beauty and elegance’ competition of the weekly Színházi Élet). At the time the film was shot, he was a recognized and successful painter. Having completed studies in Munich, Paris and Florence, and immediately before making the film, in February 1914 he staged an exhibition of 99 works at the Ernst museum. From this date, displays of the National Salon regularly included his uniquely atmospheric, fairy tale-like pictures decorated with rich ornamented fantasy. Later on, he also designed book illustrations, theatre scenery and sets, and became the most sought-after portrait painter of fashionable stars and the ruling class during the Horthy period. His star portraits can also be seen in period films. He continued to live in Hungary after 1945, but his career was broken, his assets were confiscated, and during a show trial in 1952 he was sentenced to eight years, of which he spent five years at Márianosztra. From his release to the time of his death he lived in Polgárdi, in the flat of his former steward. His art sank into obscurity for decades, but has recently been rediscovered. In 2015, Kieselbach Gallery organized an exhibition of his works and Péter Molnos wrote an important monograph of his career.

For further information, please click on the gallery below

The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man (gallery)

Shooting the film

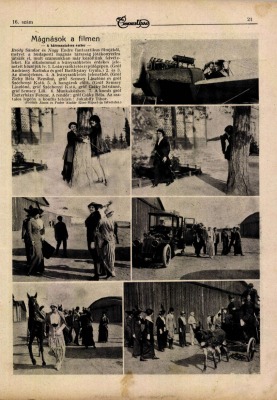

Rehearsals were arranged by Countess Gyula Andrássy in the mansions of Countess Gyula Andrássy, Countess László Semsey and Countess Imre Széchenyi as well as the Park Club on Stefánia Road. Shooting started at the end of March. The press reported in detail on the film shoot at the airfield, which was on 2 April.

“Recording of the airfield scene took place at Rákos yesterday morning and afternoon, when Count Béla Rezső Zichy, president of the Hungarian Aero Association, Dr. Ernő Massány, association director, and secretary Miklós Feleky welcomed the artistic aristocrats and showed them around. In brilliant sunshine, Countess Katinka Andrássy, heroine of the silver screen, arrived by car at the aerodrome. […] Then the Kolbányi monoplane was wheeled out of the hangar, the hero and heroine sat in it and the cine-camera did its job. The flight itself will be shot (naturally, without passengers) from the Prodám monoplane in the next few days.” (Magyarország, 3 April 1914)

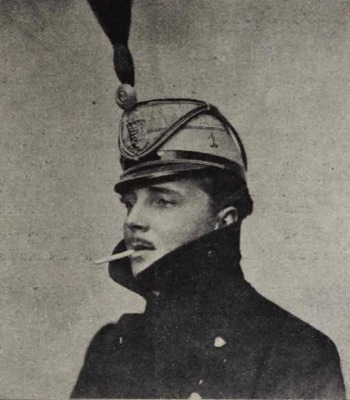

Shots of the actors actually in the plane were probably hindered for technical reasons: in general, these early aircraft had only two seats, so there would not have been enough room for the pilot, the two players and the cameraman, but it is not impossible that the unpleasant memory of the fatal accident with the Kolbányi aircraft 18 months earlier discouraged the actors from flying. The film included the first ever shots of Budapest taken from the air; these were also designed to promote Hungarian aviation. These pictures were taken from a monoplane of Prodam Guido, who was famous for having first flown above Budapest, in 1911.

The Kolbányi monoplane with Sándor Takács aboard, the first martyr of Hungarian aviation (source: Fortepan)

Press reports of the day carried relatively little about the people making the film, Kino-Riport, the company which initiated Hungarian newsreels, director Aladár Fodor and cameraman József Bécsi. These individuals partly ensured the high technical and artistic standard of the amateur production. Little is known about the financing of the film; we can only assume that the perceptive business owners of Kino-Riport, Aladár Fodor and János Fröhlich, probably also contributed to the making of the film – partly through their expertise, and partly with raw materials and laboratory space – having reckoned on public interest in the private lives of the aristocracy. They must certainly have hoped that this film would raise the profile and prestige of their recently launched company.

If this was what they planned, then they could not have been disappointed because the film attracted considerable attention from the press even while it was being made. News about preparations for the film and reports on the shooting itself were regularly carried by the trade journals and dailies. Besides the enthusiastic reports, there were articles in the left wing press that mocked the altruistic endeavours of the aristocracy: “... in the interest of the polyclinic, our magnates felt obliged to permit the huge sacrifice of their mansions being filmed, even at the cost of their wealth. Once on the path of squandering charity, they are not to be trifled with,” wrote Népszava in its edition of 22 February 1914.

First night and reviews

The film’s first night was scheduled for 23 April 1914, but for technical reasons (probably the print was not ready) it was only held on 26 April in the Liszt Academy. The first night did not go according to plan. A report by Az Est reckoned that the Liszt Academy’s Grand Hall was only half full. After the overture by László Kun’s philharmonic ensemble, the Ernő Szép prologue was recited by Margit Lánczy, member of the National Theatre. Endre Nagy’s work Aviation in Our Country was to have been given by Erzsi Paulai of the National Theatre, but she did not turn up. From the Opera House, Erzsi Sándor also withdrew, so her vocal performance was similarly cancelled. Contrary to earlier reports, Archduke Joseph did not make an appearance at the first night. Despite all these setbacks, the film was received positively in professional circles. Gyula Décsi, owner of the moving picture theatre and president of the National Federation of Cinematographers, praised it thus:

“I must report on The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man with the greatest of enthusiasm. The footage not only is of an equal standing with the most classical products of international companies, but there are also in it such plastic, truly artistic settings and photography that one searches for in pictures brought here from abroad in vain. [...] the actors play remarkably well in front of the camera. It is as though the figures of this charming piece are not amateurs, Hungarian aristocratic ladies and gentlemen, but film kings selected from the ranks of cinema artists picked from across the globe. For my part, I see the cinema career of The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man secure to the highest degree, indeed, I would go as far as to say that out of the last few years of mass productions – in which there have been genuinely massive hit pictures – a film with every right to similar success has not been seen on the market.” (Független Mozinapló, 9 April 1914/10)

The critic of Magyarország also praised the film and its actors:

“The majority of our aristocrats showed an aptitude and indeed, some revealed considerable talent. The two lead actors, Countess Katinka Andrássy and Count Gyula Batthyány in particular. Katinka Andrássy injected considerable life into the slightly shaded figure of Countess Borbála, and won over the audience with her youth and beauty. Gyula Batthyány is a fully-fledged cinema actor, his gestures and expressiveness bear witness to considerable talent.” (Magyarország, 28 April 1914)

However, the Est was somewhat negative in its report on the premiere and the film:

“The soiree started with us waiting three quarters of an hour, partly due to the need to indicate one’s aristocratic position, and partly due to disorganization. Then a director in tails turned up and announced in a quavering voice that there was a problem. Then there was a concert performance which, after a lengthy interval, was followed by a double bass. The charming Margit Lánczy had the Ernő Szép prologue in response. Endre Nagy compered, bearing the surprise with light humour, and then the hall darkened and the ‘magnates’ film’ started. The aristocrats played at being 17th century knights; their gait was neurasthenic and swaying, and the screen trembled with them. … The lead role went to the all-knowing count, Count Gyula Batthyány. The piece would have been extremely interesting had the direction been more competent ... but even so we watched with great attention the movement and life of beautiful aristocrats on the silver screen ... According to the programme, there should have been songs and recitations, but in part the players forgot to turn up, and in part the organizers forgot their cast.” (Az Est, 28 April 1914)

After the first night, the Apolló and Tivoli cinemas ran the film. The film critic of Az Est was far kinder about this, saying that the cinema premier attracted considerable interest and was far more successful than the first night. In the wake of the Budapest premier, there were screenings in several cities throughout the country, which in the final analysis was a success, although we have no information on how profitable the venture was from the aspect of the stated aim of raising money for charity. Despite the success, and the fact that it was obviously important for the young Hungarian aristocrats playing in it that this piece of cinema preserving their performances and youth should survive, The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man could not avoid the fate of the majority of Hungarian silent films as it, too, disappeared without trace.

The photo album

However, what did survive was a leather-bound photo album in which 66 photographs of scenes from the film were glued. The photos were taken by Lajos Szőnyi, primarily known as a photo reporter, and in April 1914, prior to the film’s debut a few of them were published in Új Idők, Színházi Magazin and Független Mozinapló as illustrations for film reports. The photos will certainly have been inserted in the gilded album because of the illustrious actors featuring in the film, but it remains a mystery exactly where they were right up until 1989 when (as an anonymous donation) they were registered with the library of the Film Archive.

The reconstruction

By looking through the photographs and comparing them with contemporaneous plot descriptions it became apparent that a large part of the action and most locations could be demonstrated with the surviving photographs. Thus the idea arose that we should try to breathe new life into these still shots, stringing them together onto a plotline reconstructed from extant descriptions of the film. The most useful source proved to be the film review published in Új Idők, written by Kornél Tábori under the nom de plume of Old Reporter, which is why we put the surviving photos in order relying mainly on his plot descriptions. We then added captions. We did not keep the pictures in the order they were in the album, we used a few of the shots several times.

Lacking photographs, we replaced the missing parts of the plot with explanatory texts in order to clarify the storyline. Unfortunately, there are no existing photographs of the final scenes in the film, which is why we were unable to present the wedding scene described in the 3 April 1914 edition of Magyarország: “We see the Fisherman’s Bastion as the conclusion of the play, where the Hungarian-costumed wedding procession comes out of Matthias Church, accompanying Borbála and Bálint.” We replaced the missing parts with Kornél Tábori’s humorous lines, in whose description, and as a consequence in our reconstruction, the story has a happy end: “the knight kidnaps the young countess and flees into the air. From on high, we see all of Budapest and the sapling as well, which has in fact grown into a lofty pine. It is appropriate at this point for the countess’s heart to soften, for tenacious love to triumph, and as the international movie police regulation demands, the work finishes with a harmonious exchange of vows.”

Kornél Tábori’s article was published on 19 April 1914, thus it is quite possible that he never saw the film, which was probably only completed a few days before the 26 April first night. So it is by no means certain that the story actually had a happy end. The original concept of Sándor Bródy and Endre Nagy was different. At least this is what is apparent from the preliminary review published in the paper of the Hungarian Aëro Association, saying that the authors finally went back on the happy end. According to the screenplay, at the end of the film Count Bálint wakes up and realizes he has dreamed the whole thing: “The fantasy vanishes and in the final scene Count Bálint becomes aware of the sad reality.” (Official Journal of the Hungarian Aëro Association, 1914/8-9.)

Today, we simply cannot decide whether the film had a sad end, or a happy end. On the side of there being a sad end is the original intent of the screenwriters and the fact that the demand for a happy end was not as strong in Hungarian films of the silent era as it was in the 1930s, when there were even instances where negative audience feedback resulted in a happy end being inserted, retrospectively, into the already completed film (Lila akác Purple Lilacs, 1934). In the end, we decided to go with the happy end because without photos to the contrary, a sad end could have been shown only with added complications and much explanatory text.

The aristocracy and the history of film

The Hungarian aristocracy always played an important part in artistic life: in music, primarily as patrons, in literature and the fine arts, frequently as important creative artists. This time, young Hungarian nobles contributed to the development of Hungarian film, even though this was not their intention; instead, they were motivated by charity, the chance to try a role or a new medium, and they created the first feature film of 1914. It is impossible to judge the quality of The Three-Hundred-Year-Old Man without the film, on the basis of contradictory reviews and the 66 photo stills, but it is possible to establish that as regards the genre and technical innovations, it was an important experiment and useful experience for Hungarian feature film production that was barely two years old.