Rapée, Ernö (1891–1945)

Ernő Rappaport (birth name), Ernö Rapée, Erno Rapee

composer, conductor

4 June 1891, Budapest, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

26 June 1945, New York City, New York, USA

The name Ernö Rapée is known in Hungary primarily in the world of jazz and few are aware that the world-famous conductor-composer played an important role in the history of film music, too. The serious, fragile-looking artist was highly regarded in the profession. He wrote immortal jazz melodies, revolutionized the musical accompaniment for silent films and compiled an encyclopaedia and teaching material for colleagues. He always insisted on quality and drew up a detailed theoretical treatise to his work. It is no coincidence, then, that Maestro Rapée was frequently referred to as “the little man with the big orchestra”.1

Ernö Rapée completed the National School of Music, Budapest in 1909 and from here, aged just 18, he left to seek his fortune abroad. The young man proved to be a talented pianist and conductor, working as theatre conductor in Dresden, Magdeburg and Katowice. Later on he toured Mexico and South America, then decided to set his sights on the United States. Like the majority of other immigrants, on arrival in New York he, too, had to build a new life from scratch. This is how he recalled this fraught period: “Then with a great shove, I sailed across the ocean and we docked in New York. I knew nobody. Life was difficult. But I was lucky. In my first week I wandered into a café where they were looking for a pianist. I took the job. I was paid 25 dollars a week. I remember it was an ugly, smoky, smelly joint. Mainly down-at-heel Hungarians went there, those who somehow managed to scrape together the twenty-five cents that a dinner cost. I had to play Wagner and Liszt for them. Interesting. Even in their dejection they demanded quality music. I went from café to café for six months. I always thought the next one would be better. It was not so. I didn’t earn any more and I didn’t find a better place either.”2

Rapee, who to begin with played piano in an East Side restaurant for a few dollars, began to receive ever more jobs until one day he was appointed director of the Hungarian Opera Co. The tour in America of Hungarian Opera Co. was Rapee’s first major business success and yet he didn’t stay here long.

Meeting with Roxy

(source: The Cooper Collections, Wikipedia)

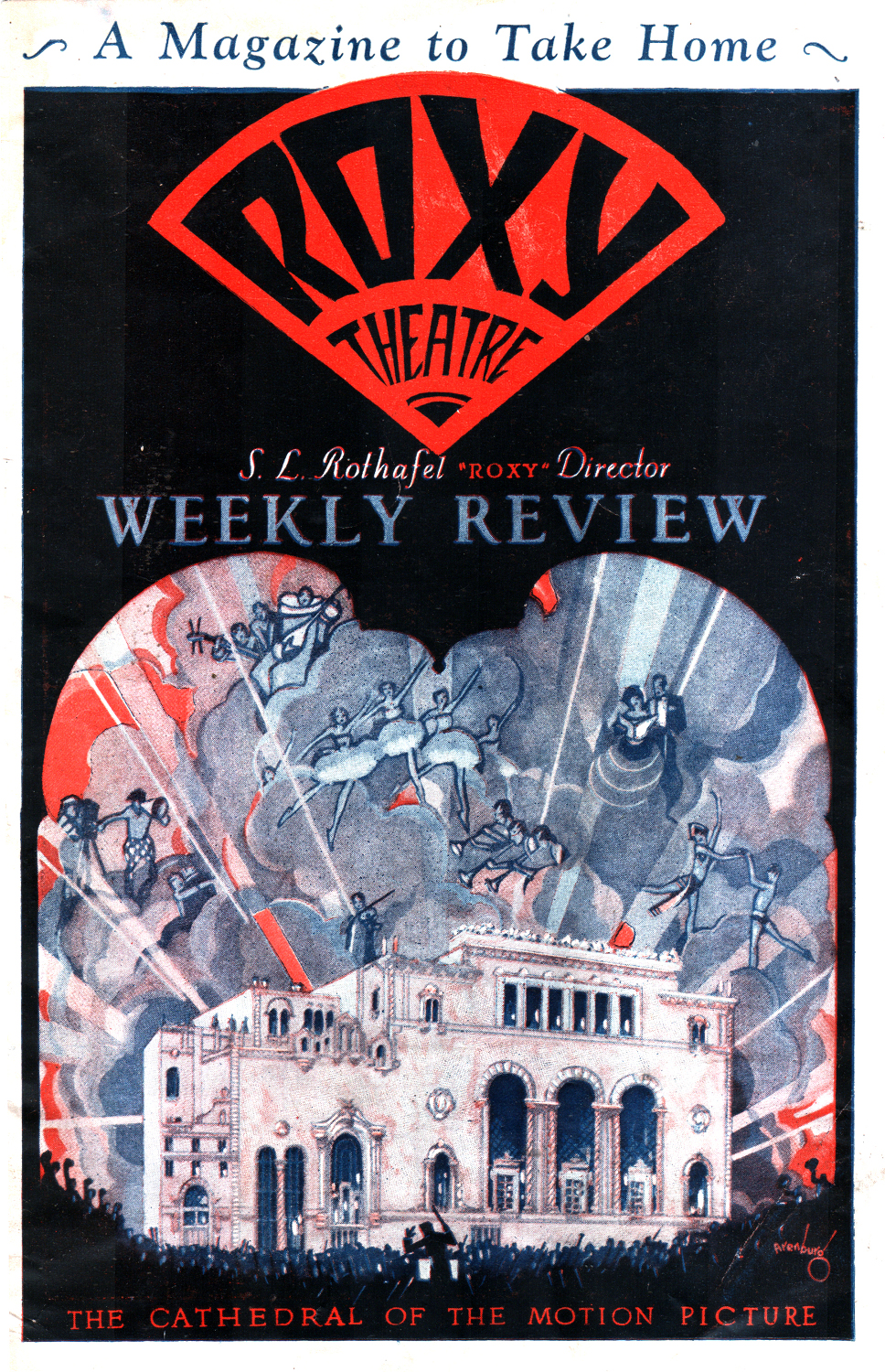

Quitting the Hungarian company, he contracted as the conductor of the Rialto Theatre orchestra. This is when he was spotted by Samuel L. ‘Roxy’ Rothafel, who was himself an immigrant of German extraction and one of the most promising New York impresarios of the day. Rothafel had moved into showbusiness in the 1910s and made his mark by introducing a new approach to cinema culture. He organized performances primarily at the Rialto, Rivoli and Capitol cinemas during which the live accompaniment integrated perfectly with the on-screen action. This was the first time that a symphonic full-size orchestra performed alongside films screened in these cinemas. The high standard of performances attracted demanding urban audiences. In 1927, Rothafel opened the legendary Roxy Theatre on Times Square, followed by Radio City Music Hall and RKO Roxy.

Later on, the careers of Rothafel and Rapee were closely intertwined. The composer-conductor with a wide intellectual horizon understood Rothafel’s plans exactly. Performances he came up with not only served as truly experiential backgrounds to the films but also worked as stand-alone musical concerts and as kind of variety show in themselves. Rapee worked at the Rivoli from 1912, and then at the Capitol cinema, while later on he conducted the hugely popular Sunday symphonic radio broadcasts from Roxy Theatre. Soon he was contracted as music director of several theatres and his 80-person orchestra was famed for giving opportunities to Hungarians.

In the mid-1920s, the conductor, who by then enjoyed a considerable reputation and was well-off, travelled to Europe at the request of UFA. There, he worked as a music consultant helping to introduce the new concept successful in the United States into German film theatres. In addition to this work he also conducted the symphony orchestra and jazz band of UFA Palast Zoo.3 During his major concert tour of Europe in 1925 he also visited Budapest where he answered journalists’ questions in Hungarian, and with a measure of nostalgia, in the first floor apartment of Duna Palace.

Rapee’s melodies

In the early 1920s, Rapee already worked for Fox, but even so his first major success as a film composer happened in Europe when he wrote music for the movies of Ewald André Dupont’s Varieté (1925) and F. W. Murnau’s Faust (1926).4 Soon thereafter he returned to America, where in the second half of the 1920s, in the late silent film era, he was particularly productive. His biggest hits frequently played even today were Diane (I’m in Heaven When I See You Smile), Charmaine and Angela Mia co-written with lyricist Lew Pollack. Diane was subsequently reworked numerous times but originally it was written for the romance movie 7th Heaven (director: Frank Borzage, 1927). This was shot as a silent film but there was also an audio version made using Movietone technique, for which he wrote the accompaniment. 7th Heaven was nominated for Outstanding Picture at the first Academy Award in 1929, and although it did not win in this category5 its success bolstered Fox Film Corporation’s position among the studios. The romantic Charmaine was similarly silent film music for the war melodrama What Price Glory? (director: Raoul Walsh, 1926), although its melody appears in many films to this day, from Sunset Boulevard (1950) to The Rum Diary (2011) and the Twin Peaks series (2017).

Rapee’s works are also special because he was one of the first composers whose film music became popular as independent hits.6

Charmaine (1927)

This successful film music led him directly to Hollywood, where – in 1930-31 – Rapee made a brief detour into the embrace of Warner studios, undertaking the music direction of numerous early sound films, for example, Little Ceasar. However, he soon returned to his true home, New York, where he was made music director of NBC, and then from December 1932 until his death, music director of Radio City Music Hall and first conductor of the Radio City Symphony Orchestra.

Diane (1927) – arrangement by Miles Davis

The musicologist

Rapee was known not only for his compositions and expertise as a conductor, but also for his achievements in music theory. The Encyclopaedia of Music for Pictures published in 1925 remains a core work to this day. It covers the theory of film music, the system of certain music themes and offers specific titles for these.

The author emphasizes the independent dramaturgical role of accompanying music, proposes how to put together an orchestra accompanying a film screening and describes those aspects to be taken into consideration during such performances. He states that it is always necessary first to illustrate the location and nationality of the story with background music in order to conjure up the right atmosphere, and then it is necessary to define a particular musical motif for each character with special attention to the love theme, wicked and humorous figures. His guide mentions those situations representing particular challenges for musicians during the movie screening, such as when several characters are present at the same time, there is a flashback in the story, but he also analyses the differences in accompanying non-fiction films such as newsreels, and feature films.

Studying the volume, it is possible to learn a lot about the characteristic topics of silent films of the period, the illustration of which represented the work of musicians from one evening to the next. Rapee approaches the issues as a true archivist and emphasizes that a professionally managed and continuously expanding music library is an indispensable part of every serious motion picture theatre. He prepares a kind of card index for this, with the help of which the conductors and musicians can easily and quickly locate those musical pieces most appropriate for the given film. The following excerpts are taken from this system as examples: People – firemen, engineers, cowboys, pirates etc.; Creatures – bees, birds, cats, chickens, dogs, fish etc.; Places – seashore, coal mine, desert, fair, asylum, mill etc.; Objects – clock, fountain, telephone; Entities – ghosts, nymphs, clowns, skeletons, witches, but he also has recommendations for music motifs related to certain countries and peoples, ambiences, illustration of music-dance scenes, and such abstract topics as prohibition.7

Rapee’s system is still used today by researchers of silent film music, his book is an important reference in the history of film music, but experts dealing with information systems and archive theory also frequently refer to it. The indefatigable conductor, composer and writer created lasting works from many aspects and it is no coincidence that he himself frequently said: “It is hard to kill a good Hungarian with work.”8

Notes

[1] Jack Banner: Music Hall Music: A Problem in Mass Culture. Motion Picture Daily. 1937. december 29., 10.

[2] Hogyan lett a szegény pesti Rapaportból dúsgazdag amerikai Rapée. Az Ujság, 1925. március 3., 8.

[3] Rapée Ernő (Ernő Rapee) Németországban és az Egyesült Államokban (1925. október – 1945. június 26.) In: Simon Géza Gábor: Magyar jazztörténet. Budapest: Magyar Jazzkutatási Társaság, 1999. 50.

[4] A Faust zenéjét Werner R. Heymann-nal közösen jegyzik.

[5] A legjobb film díját (Outstanding Picture) az első Oscar-díj átadón a Wings nyerte el, A hetedik mennyország a Legjobb rendezés - Filmdráma (Frank Borzage), a Legjobb színésznő (Janet Gaynor Diane szerepében), Legjobb forgatókönyv – adaptáció (Benjamin Glazer) díjakat vitte haza.

[6] Bővebben: Rapée, Erno: Encyclopaedia of Music for Pictures. New York: Arno Press & The New York Times, [1925] 1970. és Henry, Joshua A. – Smiraglia, Richard P.: Taxonomy and Partial Topic Map of Terms from Rapée’s Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures. Institute for Knowledge Organization and Structure, Inc., 2019.

[7] Rapee, Erno. In: Hischak, Thomas S.: The Encyclopedia of Film Composers. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015. 548.

[8] „It is hard to kill a good Hungarian with work.” Jack Banner: Music Hall Music: A Problem in Mass Culture. Motion Picture Daily. 1937. december 29., 10.

Sources

Erno Rapée. DAHR – Discography of Amercan Historical Recordings.

Rapée, Erno: Motion Picture Moods, for Pianists and Organists: a Rapid Reference Collection of Selected Pieces, Adapted to Fifty-Two Moods and Situations. New York: G. Schirmer Inc., 1924.

Rapée, Erno: Encyclopaedia of Music for Pictures. New York: Arno Press & The New York Times, [1925] 1970.

Erno Rapee az amerikai Fox-színháztrust vezérigazgatója európai körútján hazaérkezett Magyarországra. Színházi Élet, 1925/9., 44–45.

Hogyan lett a szegény pesti Rapaportból dúsgazdag amerikai Rapée. Az Ujság, 1925. március 3., 8.

Rapee Ernő magyar karmester sikere külföldön. Magyarország, 1925. szeptember 30., 2.

A magyar Rapée és Antalffy-Zsiros a newyorki rádiónál. Magyarország, 1932. december 13., 10.

Jack Banner: Music Hall Music: A Problem in Mass Culture. Motion Picture Daily. 1937. december 29., 10.

Rapée Ernő (Ernő Rapee) Németországban és az Egyesült Államokban (1925. október – 1945. június 26.) In: Simon Géza Gábor: Magyar jazztörténet. Budapest: Magyar Jazzkutatási Társaság, 1999. 50.

Rapee, Erno. In: Hischak, Thomas S.: The Encyclopedia of Film Composers. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015. 547–549.

Budapesttől New Yorkig: Rapée Ernő. In: Simon Géza Gábor: Szösszenetek a jazz- és a hanglemeztörténetből. Budapest: Gramofon Könyvek, 2016. 219.

Henry, Joshua A. – Smiraglia, Richard P.: Taxonomy and Partial Topic Map of Terms from Rapée’s Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures. Institute for Knowledge Organization and Structure, Inc., 2019.