Fejos, Paul (1897–1963)

The polymath filmmaker in whose life there was room for the glitter of Hollywood, the world of tigers and Komodo dragons, not to mention mapping mysterious Inca ruins.

Pál Fejős (birth name), Paul Fejos

director, screenwriter, set designer, producer, anthropologist

24 January 1897, Budapest, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

23 April 1963, New York, United States

The son of Dezső István Fejős, civil servant at the interior ministry, and Berta Hajnalka Novelli was born on 24 January 1897. The young boy, who spent most of his childhood in Budapest and Szekszárd, lost his father when he was just two years old. First they went to live with his maternal great uncle, and then on his death with the sibling of his father. Whereas he formed a deep attachment with the former, whom he always called ‘granddad’, the latter frightened the boy with his tyrannical nature. In a family boasting of its rarefied heritage, it was important that children be well educated so the boy was enrolled into the austere Piarist school where, however, their plans went completely astray because Pál fell in love with the theatre during amateur dramatics classes. Even though he was certain that he had found his vocation, he was enrolled into medical school. During the First World War, from 1917 he was enlisted in the ranks of the 7th Hussar regiment but later on he also served as one of Hungary’s earliest air force pilots. As is evident even in these early years, Fejős’s life was one of constant flux, his career took many rapid turns and things were no different later on.

In his person, the wisdom of the far-sighted man and the talent of the polymath combined, resulting in him bequeathing an extraordinary rich oeuvre to posterity.

Paul Fejos (source: NFI)

From organizer to designer

On Fejős’s return home from the front, in Budapest revolution broke out and the short-lived Republic of Councils was formed in spring 1919. During this period the nationalized film industry became a critical area and the architects of cultural policy made every effort to involve talented young people in organizational projects. Aged just 21, Pál Fejős was appointed head of the Scenics Department operating within the Arts Department. He was charged with ensuring the acquisition of props and costumes required for shooting and supervising the inventory. Although he proved to be an efficient administrator, this was not enough to satisfy him so he soon began to dabble in production design. Initially, the Phönix company, which was planning to film a work by Ferenc Molnár, asked him to design the sets, but this motion picture was never made because the director, Mihály Kertész, emigrated. The first film where “the magnificently grandiose sets, amongst which are lavish rooms in Rome, rich and heavily ornamented, marble-floored interiors with fountain, were made under the direction of Pál Fejős, head of scenics at the studio”1 was the movie Tláni, directed by Károly Lajthay and made by Triumph studio. The following year, in 1920, he was production designer for Omega film studio’s Chinese-themed work, O’Hara; this fact makes it evident that he was one of those professionals who were permitted to continue working even after the collapse of the Republic of Councils and he quit the country not during the wave of mass emigration in late 1919 but only after. It appears that during this time his entrepreneurial spirit was a strong as ever: in 1920, József Neumann, who also established the first Hungarian film production company, Projectograph, set up a brand-new film studio in Budapest called Mobil, where Fejős was listed as first director.

Silent adventurers

During the silent movie era, Fejős directed six feature films, two anthology films and a few shorts in Hungary. Typically, his films have thrilling, entertaining plots made in the mould of American motion pictures and designed for mass consumption. The screenplays frequently feature fantasy elements although these were difficult to get passed by the rigorous censor so despite a promising start, this trend in Hungarian films quickly withered. Pán (1920) plays out in an American theatre setting where a statue used as a stage prop comes to life due to the irresistible nature of a famous dancer. His next film, Lidércnyomás (Lord Arthur Saville’s Crime, 1920), is considered by film experts to be an experiment to introduce the Expressionist style in Hungary.2 Sadly, just like Fejős’s other Hungarian silent films, this too has been lost, thus we have no way of knowing how effectively he managed to realize the story adapted from the novel by Oscar Wilde who was hugely popular in the country at that time. Újraélők (The Relivings, 1920) revolves around the subject of reincarnation. Its heroine, Ilona Mészáros, travelling back to the Middle Ages, must learn from her mistakes so as not to repeat them in the present. Actress Mara Jankovszky played Ilona Mészáros; she appeared in several of his films and was married to Pál Fejős between 1921-1924. A newspaper reported on the next film, A fekete kapitány (The Black Captain), thus: “All of Budapest is talking about the latest trickfilm from Mobile studio, ‘Fekete kapitány’. Lead artists Gusztáv Pártos, Lajos Gellért and Mara Jankovszky are to be found on the roof of the New York Palace, on dizzyingly high fire ladders, while the American police force races around in cars. A particular feature of the film is that a specially built American workers’ hostel is blown sky high while equestrian chase sequences would put American cowboys to shame.”3 The film’s creators planned on making a thriller series out of the story but it all came to nothing because the Hungarian authorities found the movie more than enough and banned A fekete kapitány.

It is likely that this and similar failures played a large part in Fejős eventually deciding to take a different path. He founded his own film studio, Premier, where he planned to make quality adaptations of literary works. His film version of János Arany’s poem Az ünneprontók was never shot but this was not the case with Pique Dame (1921) based on the Pushkin novel, although the production, considered weak even by Fejős, was almost certainly never screened. At this time, Hungarian filmmaking was in serious financial and organizational distress, cinemas were flooded with imported pictures and all trace of the explosive productivity of the second half of the 1910s was gone. Fejős tried his luck with an anthology film built on a popular figure of the time, Arsene Lupin; this was a unique genre mixing stage scenes performed live and motion pictures. Arsene Lupin utolsó kalandja (1921) has similarly been lost but film historian Gyöngyi Balogh, basing her deductions on the remarkable resemblance of contemporary descriptions, suspected that this thriller may have recycled previously unreleased footage from A fekete kapitány.4

The Stars of Eger (source: Hangosfilm)

Since during these years filmmaking had become near impossible, Fejős organized a live-action Passion tale at the request of the assistant clerk of Mikófalva near Eger. Stage sets were borrowed from the Opera House for the large-scale open-air performance that demanded huge organizational energy. Costumes were made based on the painting Christ Before Pilate by Mihály Munkácsy. The Passion attracted an audience of 25,000 and although it was not an unqualified critical success, it exercised a significant impact in shifting Fejős’s interest towards folk culture and anthropology. After a brief trip to Paris, the by then recognized director made his last silent film in Hungary, Egri csillagok (The Stars of Eger, 1923) adapted from the popular novel by Géza Gárdonyi. Shooting was not without its own scandal because soldiers acting as extras in scenes filmed in Matthias Church, Buda were drunk and desecrated the church. However, all difficulties were overcome, László Angyal composed original music for the movie and the non-public premiere was held in Gödöllő attended by Regent Miklós Horthy and his family (the public premiere was in Eger on 14 December). Unfortunately, again this film is lost but a few surviving frames show what it may have been like; in one frame, for example, we can see Mara Jankovszky playing the role of Éva Cecey striking a heroic pose, in chain mail vest and with drawn sword.

Taking a new road

In 1923, Fejős left Hungary and arrived in New York on board the ocean liner Leviathan on 15 October. He spoke only a few basic English phrases and the few dollars in his pocket were soon spent. “Then came a rather bitter period of about three months, in 1923. I wanted to work but I hadn’t the slightest idea where or how to find work. To compensate for this, I believe, every morning I got up at 6:30 for no reason – I am normally a late riser – but I needed to show myself that I was trying. I lived on 72nd Street West, and I started out every morning from there and walked clear down to the Battery and then walked back from the Battery again, which is a long, long distance. During the time of all these walks, I had the wildest daydreams. I thought that somebody would suddenly look at me on the street, stop me, and tell me this is the man they wanted since I don’t know when.”5

To start with, Fejős accepted gruelling manual jobs for just a few dollars a week. Soon, however, as had happened earlier when in a tight corner, he used his medical training in Hungary as a lifebelt and took a post as laboratory assistant bacteriologist at the Rockefeller Institute. Although he adored his work, he didn’t need to think twice when, apparently at the author’s recommendation, the Guild Theatre contacted him to help them create an authentic Hungarian environment for the staging of Üvegcipő by Ferenc Molnár.

From the orange grove to Universal

(source: Criterion)

From here there was no stopping and Fejős was soon on his way to Hollywood where in 1926 he had to start again, this time for the third occasion, from scratch. For a while, he wandered around the studios in Los Angeles without contacts or cash, living mainly on fruit stolen from nearby orange groves. This went on until one day, when hitchhiking, he was given a lift by Edward M. Spitz, who was similarly a resolute, young producer. Spitz offered him 5000 dollars and a stake in the budget of a period feature film to make the film they both hoped would make their names. This was The Last Moment (1928). After watching the movie, Charlie Chaplin, together with all of Hollywood, proclaimed the newly discovered Fejős to be a genius. It is the chronicle of a suicide in which a drowning man sees his life flashing before his eyes. The novelty of the story told in expressive style, with dramatic visuals and no subtitling, fascinated audiences, who did not even suspect that the kaleidoscopic atmosphere was due in part to the daily changing scenery received as a favour and the spontaneous ideas born out of an extremely limited budget. Unfortunately, not a single copy of The Last Moment has survived but to this day it is one of the most sought-after titles of lost silent movies in the United States.

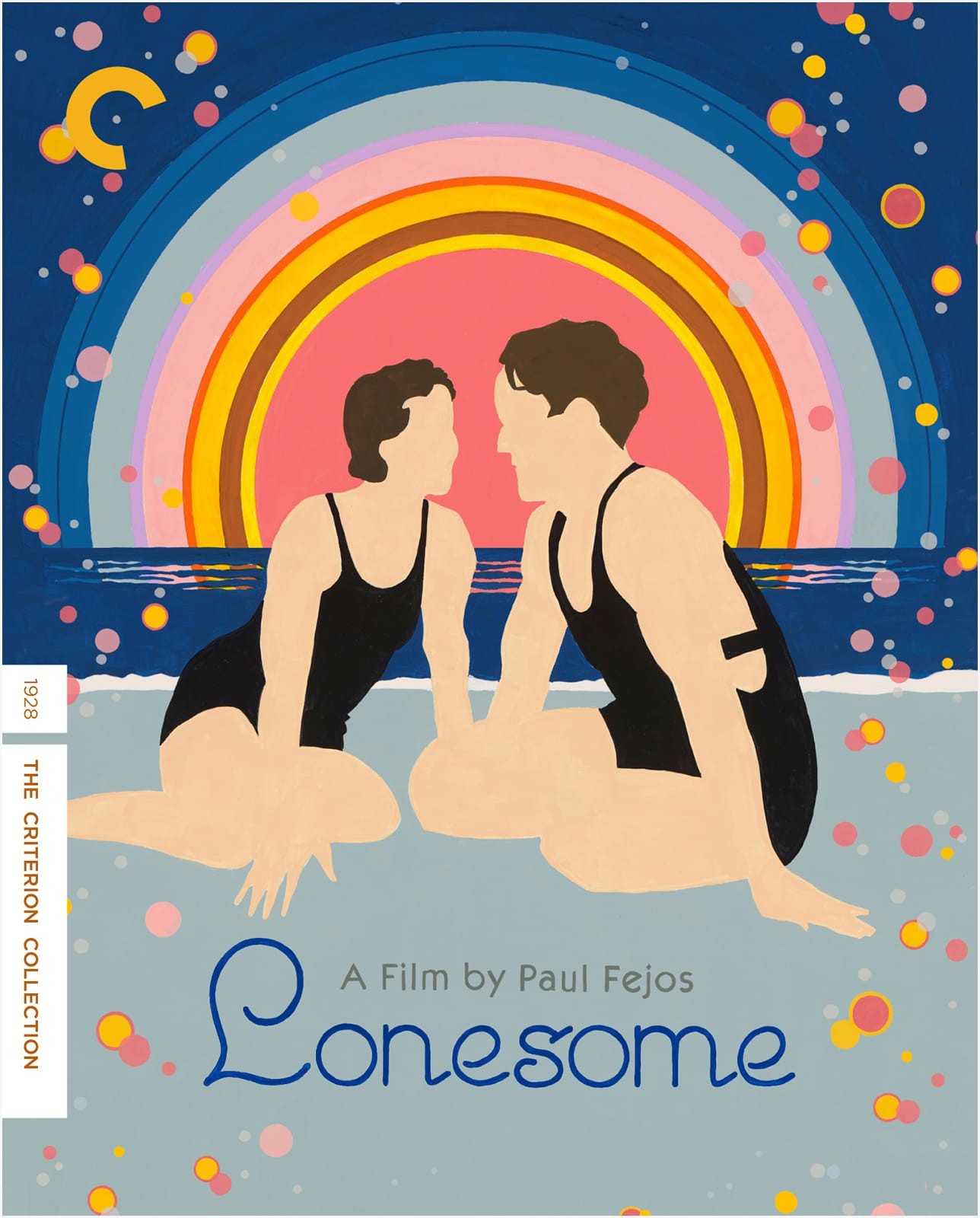

After this explosive start, Fejős was contracted by Universal on the recommendation of Carl Laemmle, Jr. Fejős insisted that he be allowed to choose the screenplays and Lonesome (1928), which he shot from a film concept of just a few pages and that cost him only 25 dollars, became a classic. The film is the story of a day in the life of two young workers from New York, played by Glenn Tryon and Barbara Kent. They live solitary lives in the big city until they accidentally meet and immediately fall in love. They spend an afternoon together at the beach but later lose sight of each other. The most frequently cited scene is set in Coney Island amusement park where the two desperately try to find each other, without success. Finally they return home separately, but to their greatest astonishment it turns out that they live close to one another. The film effectively communicates the buzzing energy of the metropolis and a sense of urban alienation, almost certainly inspired by Fejős’s own personal experiences in New York. Lonesome was made in both silent and talkie versions, and some scenes were tinted using the stencil technique.

Fejős’s debut film at Universal was a considerable critical and financial success. This was followed by the sinister drama The Last Performance (1929), with the lead played by film star Conrad Veidt who similarly had emigrated from Europe. The film is about a love triangle between Erik the magician, his beautiful assistant and a young thief. The first half of the plot is set in Budapest. This was another movie made at the time of the transition from silent to sound so audio scenes were also distributed using the Movietone technique. According to news reported in the Hungarian press, a Hungarian version of the film was also made in Hollywood, in which Béla Lugosi dubbed Erik’s lines.6 The next film was Broadway (1929), important primarily from a technical aspect. The cinematographer was Hal Mohr, who earlier was cameraman on what is considered the first sound film, The Jazz Singer, later on he won two Oscars and he designed a huge camera crane that allowed him to take particularly dynamic footage.

Over time, Fejős’s relations with Universal became ever more strained since his films did not generate the expected revenues while he felt restricted in his artistic expression. He very much wanted to make an adaptation of All Quiet on the Western Front but he was not given the opportunity, while he worked on several other projects that were in the end passed to others. A couple of examples: Captain of the Guard (La Marseillaise, 1930) and King of Jazz (1930). Finally, he did what he had done before (and which made him somewhat unpopular with employers) and suddenly walked out of Universal to sign up with another studio. He didn’t stay long with MGM, either, just enough to film the French and German versions of The Big House (1930), the latter shoot being visited by Albert Einstein himself.

Despite his many successes, Fejős did not feel totally at ease in Hollywood. His maverick style did not sit well with the strict film industry rules and he felt himself to be somewhat of an outsider when viewing America. This is clear in his thoughts on the psychological motives of American film published in Filmkultúra in 1933: “In general, the content of American film is considered extremely naïve, even stupid. I have to state that American film is neither naïve or stupid, but consciously naïve and consciously simple-minded. This difference between American and European film starts from the fact that European film is first and foremost entertainment, while American film is morphine, a necessity of life, something without which America could not exist for even a single day. It is my firm and serious conviction that if all the movie halls closed down, America would become the scene of a bloody revolution within two weeks. American film is not merely entertainment but it is an economic, political problem, propaganda, not theatre, not art, instead a purely economic weapon, a political issue.”7

European years

Spring Shower (source: NFI)

On his return to Europe he went to Paris where he signed an agreement with Braunberger-Richebé studio and directed the first sound version of Fantômas (1932). Then he returned to Hungary on a commission of the French company Osso, shooting Tavaszi zápor (Spring Shower, Marie, légende hongroise, 1932) and Ítél a Balaton (The Waters Decide, Tempétes, 1933) in Hungarian and French. Tavaszi zápor was filmed partly in Hunnia studio and partly in the village of Boldog, Heves county, that had maintained its folk traditions. The lead role in both versions was taken by the French actress Annabella. The film screenplay was originally bought by Universal from Ilona Fülöp who lived in the United States (in 1928, it was announced that Fejős would direct the film). The screenplay had to be acquired from the American studio for the European production. The film tells the story of a maid who is seduced by the lordship’s bailiff and becomes pregnant so she is forced to leave the village. She gives birth in the city but the Court of Guardianship uncovers her secret and removes the child from her care. Mari has a breakdown and dies but she protects her daughter from heaven. When, years later, an attempt is made to seduce the young girl, the mother sends a downpour to earth, which halts the impending tragedy. The film is one of the outstanding works of early sound production but it is exciting primarily from the visual aspect. Its camera movements and editing are dynamic, it uses many on-location shots and relies heavily on folkloristic elements. Cinematographers István Eiben and Peverell Marley later went on to work with Mihály Kertész and Endre Tóth in Hollywood. French Impressionism had a strong impact on the atmosphere of Tavaszi zápor but it also includes elements that came to fruition in Italian neo-Realism. Fejős intended the film for the American market because he believed that the exotic nature of the Hungarian countryside would be exciting for an overseas audience. At the same time, he never renounced his European art movie ambitions either. “Just as those expedition films which imported the exotic enjoyed massive public interest in Budapest, so film which is exotic from the point of view of America has an audience in America, too. That is why I made a Hungarian film despite the fact that thousands criticised me saying I was again making a peasant film; but I made this film for America in order to start something whereby we approach art. I am not saying that Tavaszi zápor is art, at most it has something to do with art. I know it has a lot of kitsch; but it is impossible to give an artistic film to America from one day to the next. Because the film contains something exotic, America will forgive it for having something other than in American film.”8

Perhaps it was due to this imbalance that contemporary Hungarian audiences did not take to the film, while its position in Hungarian film history has since been reassessed. Another sound film made by Fejős in Hungary, Ítél a Balaton, is a Romeo and Juliet tale set on the lake. It was made in Hungarian, English, German and French versions. The fisherman legend shot at original locations, on Tihany peninsular, conventionalized the image of the Hungarian countryside to an even greater extent, but still some scenes have enormous dramatic power.

After these, Fejős never worked again in Hungary but he continued directing in Austria. This is where he shot Sonnenstrahl (Together We Too, 1933), in which two young residents of Vienna (played by Annabella and Gustav Fröhlich) decide not to commit suicide after all. Instead, they discover the beauties of life together. The subject of suicide is a recurring motif in Fejős films, which is no coincidence because as revealed in the biography written by John W. Dodds and some interviews, in those situations when his life lost direction, the director was often preoccupied with the thought of killing himself. On the other hand, his other Austrian film, Frühlingsstimmen (1933), is a light-hearted musical comedy featuring Szőke Szakáll and several other Hungarian stars.

Magicians and lizards

Fejős’s life took another turn in the second half of the 1930s because in 1934 he was contracted by the Danish film studio Nordisk that was working on reviving its former glory and international reputation. Here he made three feature films, the romantic comedy Flugten fra millionerne (Flight from the Millions, 1934), the melodrama Det gyldne Smil (The Golden Smile, 1935) and Fange Nr. 1 (1935), none of which were real hits. He found the constraints of the traditional film industry increasingly hard to put up with, which is why he soon notified the management of Nordisk of his shock intention to quit directing all together. According to his recollection of events, he was then offered the chance to choose any location in which to shoot films and the company would cover all expenses.

Fejős, pointing randomly at a map, hit on Madagascar and he was hugely surprised when they agreed.

Sailboats of the natives of Macassar, 1939

He was delighted with the chance to test himself in a new area where instead of a feature films, he could work on educational culture films along with cameraman Rudolf Frederiksen. Between 1935-1939 he organized expeditions to distant lands first under contract with Nordisk, and later with the Swedish Svensk Filmindustri, where he made ethnographic documentaries on the lives of the native inhabitants. Madagascar was followed by the Seychelles, Indonesia and East Asia. The films became important documents on the lives of native tribes, Fejős and colleagues won the trust of inhabitants who allowed them to film everyday life and tribal rituals. The Bilo follows the burial ceremony of a tribal chieftain in Madagascar, Våra Fäders Gravar (The Stones of Our Fathers, 1935) is also about burial culture, Skönhetssalongen i Djungeln (Beauty Parlour in the Jungle) presents the hair styles of the Bara, and two films were also made about tribal dance culture (Danstavlingen i Esira, Dance Contest in Esira, 1936; Djungeldansen, Jungle Dances, 1937). It is interesting to note that the films were shot with silent cameras and sound was added later. Fejős’s colleague, the composer Ferenc Farkas, recalled that the background music to the pictures in Madagascar proved a particular challenge since they had no original audio, and finally he could only resolve this using audio material from the Berlin phonogram archive.9 The documentary filmmaker was no longer an outsider; in order to enhance the dramatic impact, Fejős organized certain scenes for the camera. Recalling a crocodile hunt, he said: “Many of the scenes in the films are deceptions and artificially produced … No crocodile is that much of an actor that it waits around to be killed in front of the camera … For that reason, our crocodile hunt among the natives was done like this: first I shot a crocodile, and using the dead crocodile we then did the scenes...”10

Of the films made in this period, the most interesting was Man och kvinna (1940), directed by Fejős and Gunnar Skoglund. The story containing fictional elements begins in Sweden where members of a family are debating the value of a handful of rice. We then travel to the rainforest of northern Siam where we follow the struggles of a couple living there. Zsolt Pápai, writing in Filmvilág, vividly illuminates how this film fits into his oeuvre: “The lame couple battle with the tiger demon, struggle against the elements and fight their own half-heartedness – compared with earlier films, only the milieu changed, the central figures remained similar. Starting with Lonesome, Fejős’s protagonists are frequently apparently fragile yet in reality adamantine characters, whose moral fibre mainly derives from the fact that even in the most chaotic situations, they are able to believe unconditionally in a new start, sometimes even naively. Fejős writes his own fate into the stories of these characters.”11

On his travels, Fejős not only made films but collected valuable ethnographical objects. He returned from Komodo Island with Komodo dragon lizards captured for the zoos in Copenhagen and Stockholm. On one of his trips he met the Swedish industrialist Axel Wenner-Gren, founder of Electrolux, and this proved decisive for both of them: not only because Fejős saved Wenner-Gren’s life on a tiger hunt but because after this Wenner-Gren generously funded later tours, and increasingly systematic anthropological research, by Fejős. During 1940-1941, he primarily travelled to Peru and the Amazon Basin where he studied the lifestyle of the native inhabitants and mapped the ruins of Inca cities found in the vicinity of Cordillera Vilcabamba. In 1940, Fejős made his last documentary, Jagua (Yagua), on the migration life of the little known and isolated Yagua tribe, and then he wrote a book about them, Ethnography of the Yagua (1943).

On his return to the United States in 1941, he was appointed research director, and then later chairman of the Viking Fund set up by Wenner-Gren. The aim of the foundation was to support anthropological research. However, work did not start smoothly because Wenner-Grent was blacklisted for a time after being accused of collaborating with the Nazis. This charge proved to be false and the foundation, which meanwhile took on the name of the founder, still operates to this day. Fejős made significant contributions here as a science organizer identifying projects worthy of funding.

For example, he helped Willard F. Libby in the development of carbon isotope archaeological dating, for which Libby was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1960. Furthermore, ground-breaking anthropological research in Kenya by Louis Leakey was conducted with the backing of the foundation.

Professor Fejős

Annabella and Fejos (source: NFI)

Between 1942 and 1944, Fejős taught at Stanford University although he also held lectures at Yale, Columbia and in military units leaving for Far East postings. Students enthused about his classes because, with the assistance of dramatic role playing, he modelled what sort of problems and ethical dilemmas could occur in areas far from civilization, surrounded by native tribes. He captured the imagination of the public with his broad experience and authenticity, so it was not even apparent that he came to the field of science from a totally different direction. Spirituality was an important part of his character, he was passionately interested in primitive rites, “he was magically attracted to the old, patinaed cities, he was tireless in learning about them”12.

It is no coincide that the topic of death, the transition between worlds, frequently appeared not only in documentaries but in his feature films, too. Recollections also mention his sarcastic humour and his particularly perceptive expressiveness, although he himself termed his own English “baseball English”. Fejős was most usually described as an intelligent, warm-hearted and generous person yet someone still capable of passionate outbursts. It was typical of him that he wound up tasks as rapidly as he did relationships if they proved not sufficiently inspirational. After Mara Jankovszky, he married a further three times and legends circulated about his romantic adventures. One, perhaps the best known, is that he covered the beautiful Annabella, lead actress of Tavaszi zápor, with a shower of roses dropped from a plane.

Burg Wartenstein, Austria (source: Wikipedia)

After 1939, he never returned to Hungary and although he received an invitation from the Ministry of Education in 1956, he couldn’t travel due to the outbreak of the Revolution. In 1957 he began to establish the European headquarters of the Wenner-Gren Foundation in the picturesque castle of Burg Wartenstein in Austria. This became the last important location of his life, where from time to time an inspiring company gathered and fascinating anthropological conferences were staged.

Fejős died after a lengthy illness in New York in 1963. His ashes were scattered – according to his will – by his last wife and colleague, Lita Binns, from the tower of Burg Wartenstein. Commissioned by Hungarian Radio, his friend and colleague, the composer Ferenc Farkas, wrote Planctus et consolationes in his memory. His films are occasionally screened in the retrospective programmes of international festivals and the 100th anniversary of his birth was commemorated at the film festivals in Taormina and Göteborg. In 2010, Lonesome was added to the National Film Registry, which includes American films reckoned to be of outstanding cultural and artistic significance and as such worthy of careful preservation. Studying the career of Pál Fejős that spanned continents and vocations is no simple matter because his life reflects different aspects in different periods and countries. His oeuvre perfectly illustrates the international nature of the film industry and science, as well as how one curious and talented individual could contribute to the cultural heritage of several nations.

Notes

[1] Halló, mi újság? Új filmvállalat. Színházi Élet, 1919/50., 27.

[2] Balogh Gyöngyi: Fejős Pál magyarországi pályakezdése. Filmkultúra, 2004 (online).

[3] Fekete kapitány. Mozgófénykép Híradó, 1920/39.

[4] Balogh Gyöngyi: Fejős Pál magyarországi pályakezdése. Filmkultúra, 2004 (online).

[5] John W. Dodds: The Several Lives of Paul Fejos. A Hungarian-American Odyssey. The Wenner-Gren Foundation, 1973. 12.

[6] Magyarul beszélt a mozivászon Hollywoodon. Pesti Napló, 1929. december 29., 34.

[7] Fejős Pál: Az amerikai film lélektani motívumai. Filmkultúra, 1933/2., 3.

[8] Fejős Pál: Az amerikai filmről (Nyugat-konferencia). Nyugat 1932/24., 588.

[9] Farkas Ferenc zeneszerző visszaemlékezése. Fejős Pál összeállítás. Filmkultúra, 1967/6. 57.

[10] Idézi Andersen, Jesper: Under the Tropical Sun – Paul Fejos’s Film Expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles 1935-36. Kosmorama #266 (www.kosmorama.org), 2017. A cikkben gazdag képanyag mutatja be Fejős Pál expedícióit.

[11] Pápai Zsolt: Aranypolgár, Budapestről. Filmvilág 2006/01, 40.

[12] Farkas Ferenc zeneszerző visszaemlékezése. Fejős Pál összeállítás. Filmkultúra, 1967/6. 56.

Sources

Halló, mi újság? Új filmvállalat. Színházi Élet, 1919/50., 27.

Fekete kapitány. Mozgófénykép Híradó, 1920/39.

Magyarul beszélt a mozivászon Hollywoodon. Pesti Napló, 1929. december 29., 34.

Fejős Pál: Az amerikai film lélektani motívumai. Filmkultúra, 1933/2., 3–4.

Fejős Pál: Az amerikai filmről (Nyugat-konferencia). Nyugat 1932/24., 583–588.

A trypanosomától a Tavaszi záporig. Színházi Élet, 1932/14., 21–24.

Dr. Entz Géza: Magyar utazó Komodó szigetén, az óriásgyík hazájában. Természettudományi Közlöny 1939. 1093. füzet. 141–153.

Fejős Pál (Premier Plan). Filmkultúra, 1967/6, 48–63.

John W. Dodds: The Several Lives of Paul Fejos. A Hungarian-American Odyssey. The Wenner-Gren Foundation, 1973.

Fejős Pál (1897–1963). Filmspirál, X. évf. (2004). 2. sz.

Balogh Gyöngyi: Fejős Pál magyarországi pályakezdése. Filmkultúra, 2004 (online).

Büttner, Elisabeth: Paul Fejos Die Welt macht Film. Vienna: Verlag Filmarchiv Austria, Wien, 2004.

Koszarski, Richard. "'It's No Use to Have an Unhappy Man': Paul Fejos at Universal." Film History: An International Journal 17, no. 2 (2005): 234-240. doi:10.1353/fih.2005.0025.

Andersen, Jesper: Under the Tropical Sun – Paul Fejos’s Film Expedition to Madagascar and the Seychelles 1935-36. Kosmorama #266 (www.kosmorama.org), 2017.

Pápai Zsolt: Aranypolgár, Budapestről. Filmvilág 2006/01, 37-40.